When I first started teaching college composition 6 Autumns ago, I threw Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Letter From a Birmingham Jail" onto the syllabus mainly because it was a famous essay and I was a last-minute hire still trying desperately to flesh out a course plan. In my painful naivety, I taught "Letter" like a historical artifact, a relic from some bygone and incomprehensible era--fantastically well-written of course and well worth modeling, but fundamentally dated. The students responded well to it so it stayed on my syllabus; nevertheless I still felt slightly guilty, that I hadn't assigned a selection that was more contemporary, more "relevant."

But then Trayvon Martin happened, and Michael Brown, and Tamir Rice, and the Ferguson riots and the Baltimore riots and etc and etc and etc, and it became sadly clear to me that there was nothing dated about MLK's message at all, that for all our lip-service to his memory, his fundamental message is still as urgent as ever.

Then Election 2016 happened. Now "Letter From a Birmingham Jail" is my manifesto.

Early in this essay, he writes, "In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices are alive, negotiation, self-purification, and direct action." I am now entering my self-purification step, as I prepare myself for what will come next, examining my motivations, removing my fear and anger, considering what my responses should be, strengthening my commitment, contemplating how I can do the most effective good. Self-purification is no longer something that once happened, but must still happen.

Teaching this essay, I had often praised to my students how MLK, despite having every reason and justification to lash out viciously at his critics while he sat in jail on trumped-up charges, nevertheless still engaged with them respectfully, kindly, friendly, in love and charity and brotherhood, all the while still remaining uncompromising, unyielding, and outspoken in his convictions--he sincerely sought to persuade, not just shout. I will now be meditating on how to consistently perform such a feat myself. Following the admonition of Christ, I must always love my enemies, no matter how vociferously I disagree with them, no matter how many people they hurt, including me.

I will not condemn protests but consider their causes; forswear the path of the "white-moderate" more committed to peace than justice; become an extremist for love and not hate in the face of a resurgent White Supremacy (yes, they had always been there, I know; in a perverse sense, it's almost a relief to have them back out in the open, where we can see them).

It used to be a sterile intellectual exercise for me to wonder whether I would have supported the Civil Rights movement had I been alive in the '50s and '60s--of course I hoped I would have been, but one can never be certain, what one would have been like, how one would have been raised. But we no longer need to wonder now, do we; in fact, as protests and KKK parades sweep the nation, we can prove with whom we stand right now. I will forthwith be teaching "Letter From a Birmingham Jail" accordingly.

I started teaching college composition the same year I started this silly little blog; I may take a break from writing here awhile--or, I may need to express myself here more than ever, who knows, I haven't decided yet, I've never decided yet. But either way, whether this is a final sign-off or but a brief pause, in the words of Dr. King:

"Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial

prejudice will soon

pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear drenched

communities,

and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine

over our

great nation with all their scintillating beauty.

"Yours for the cause of Peace and Brotherhood,

Martin Luther King, Jr."

Sunday, November 13, 2016

Wednesday, November 2, 2016

The Last Time the Cubs Won the World Series...

I of course can only put it in temporal terms that would most resonate with me personally:

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, TS Eliot was still at Harvard, Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock not even a twinkle in his eye--and it would be far longer before the Cubs would again dare disturb the Universe.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Ernest Hemingway was 9--the Sun would not Also Rise over the Cubs for another century.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Ezra Pound still hadn't arrived in London, let alone turn to fascism (a word that didn't exist yet)--there were still no apparitions of these faces in a crowd, Petals on a wet, black bough.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Gertrude Stein had yet to self-publish Three Lives--A Rose was not yet a Rose was not yet a Rose was not yet a (Pete) Rose.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Virginia Woolf hadn't even started work on her first novel yet--for that matter, she still couldn't vote or legally inherit property, rights she would obtain before the Cubs saw another pennant.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was still alive and writing new Sherlock Holmes stories--he would solve more mysteries in the 20th century than the Cubs would win series.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Marcel Proust had not started In Search of Lost Time--For a long time he still went to bed early, as did the Cubs' repeated playoff's hopes.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Picasso was only barely past his Blue period--though the Cubs, unbeknownst to them, had only begun theirs.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Bloomsday was just another forgotten Thursday--History was not yet a nightmare from which the Cubs were trying to awake.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Ireland was still entirely part of the UK, William Butler Yeats had no notion of one day memorializing the Easter Rising, James Joyce had only just barely ditched work on Stephen Hero for A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and George Bernard Shaw had yet to write Pygmalion, the precursor to My Fair Lady--Ireland made more progress in 107 years than did the Cubs.

That is, the last time the Cubs won the World Series, the term "Modernist" did not yet exist, nor did any of the texts it would eventually get applied to.

In short, the last time the Cubs won the World Series, my entire dissertation topic didn't even exist yet!

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, TS Eliot was still at Harvard, Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock not even a twinkle in his eye--and it would be far longer before the Cubs would again dare disturb the Universe.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Ernest Hemingway was 9--the Sun would not Also Rise over the Cubs for another century.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Ezra Pound still hadn't arrived in London, let alone turn to fascism (a word that didn't exist yet)--there were still no apparitions of these faces in a crowd, Petals on a wet, black bough.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Gertrude Stein had yet to self-publish Three Lives--A Rose was not yet a Rose was not yet a Rose was not yet a (Pete) Rose.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Virginia Woolf hadn't even started work on her first novel yet--for that matter, she still couldn't vote or legally inherit property, rights she would obtain before the Cubs saw another pennant.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was still alive and writing new Sherlock Holmes stories--he would solve more mysteries in the 20th century than the Cubs would win series.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Marcel Proust had not started In Search of Lost Time--For a long time he still went to bed early, as did the Cubs' repeated playoff's hopes.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Picasso was only barely past his Blue period--though the Cubs, unbeknownst to them, had only begun theirs.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Bloomsday was just another forgotten Thursday--History was not yet a nightmare from which the Cubs were trying to awake.

The last time the Cubs won the World Series, Ireland was still entirely part of the UK, William Butler Yeats had no notion of one day memorializing the Easter Rising, James Joyce had only just barely ditched work on Stephen Hero for A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and George Bernard Shaw had yet to write Pygmalion, the precursor to My Fair Lady--Ireland made more progress in 107 years than did the Cubs.

That is, the last time the Cubs won the World Series, the term "Modernist" did not yet exist, nor did any of the texts it would eventually get applied to.

In short, the last time the Cubs won the World Series, my entire dissertation topic didn't even exist yet!

Tuesday, November 1, 2016

On "Checking In" at Standing Rock

So early yesterday morning, I opened up Facebook to see that one of my friends had checked in at Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota! Not only one, but several! In fact, the list kept on growing! At first it appeared that a bunch of my old classmates at University of Iowa had taken a road trip together, but then I saw folks checking in from Chicago, Seattle, and even L.A.! Overwhelmed, I considered how the most I had done so far is donate a few bucks to their legal defense fund, while these courageous souls had actually put their own physical bodies in harm's way—

Except no, none of them were physically at Standing Rock at all, they had only "checked in". Some sort of social media awareness campaign/solidarity strategy against the local Sheriff's office (though why the Sheriff would need to comb through FB check-ins to find all the protestors they had just arrested—or why protestors risking their lives would check into FB in the first place—I confess is beyond me). And who knows, maybe it actually worked, or was at least useful in raising awareness and putting pressure upon the powerful or what have you.

But you'll understand if I still felt a little deflated. Facebook activism is to real activism what Facebook life is to real life.

Except no, none of them were physically at Standing Rock at all, they had only "checked in". Some sort of social media awareness campaign/solidarity strategy against the local Sheriff's office (though why the Sheriff would need to comb through FB check-ins to find all the protestors they had just arrested—or why protestors risking their lives would check into FB in the first place—I confess is beyond me). And who knows, maybe it actually worked, or was at least useful in raising awareness and putting pressure upon the powerful or what have you.

But you'll understand if I still felt a little deflated. Facebook activism is to real activism what Facebook life is to real life.

Sunday, October 23, 2016

Edinburgh, Scotland

I was about to insist that it should really be spelt "Edinborough" if they're going pronounce it that way--but then I remembered that "-ough" has 3 different renderings based on if it's prefixed by a t-, thr-, or b-, so I let it alone and reminded myself that English is basically 2 steps from Chinese anyways.

My wife worked a trip to Edinburgh, Scotland this weekend, and despite having to be re-routed through a number of totally different airports, I was able to join her and sight-see for a day.

The Scottish secession vote was just 2 scant years ago (and on a side-note, I'm genuinely curious as to how big the Venn Diagram overlap is between those who opposed Scottish independence and those who voted for the Brexit--and vice-versa), and given the specific economic grievances the Scottish National Party held against merry ol' England, I guess I had kinda assumed that Scotland must really suck or something. And perhaps outside the capitol, things are more sketch.

Nevertheless, I was still so unprepared for just how lovely Edinburgh is! The pristine, clean streets, the dazzling diversity of architecture from Medieval to Modernist, the bag-pipers busking on the streets, the Halloween decor simultaneously exported to and imported from the United States (now there's the paradox of post-colonialism in a nutshell!), the lush green trees tinged with autumn leaves--it was rejuvenating, is what it was.

Edingburgh Castle was of course the highlight, and everything else was a cherry on top--but there were still lots of cherries. I was especially enamored with the Sir Walter Scott Memorial; I've seen a number of dead-author's placards by now, but there are Kings and U.S. Presidents with less elaborate monuments than Scott's.

My middle-name is derived from the clan MacLeland, my Dad's Mother's line. As in Denmark, I was again left wondering: does the weather here feel homey cause it reminds me of Washington, or is it the other way around?

My wife worked a trip to Edinburgh, Scotland this weekend, and despite having to be re-routed through a number of totally different airports, I was able to join her and sight-see for a day.

The Scottish secession vote was just 2 scant years ago (and on a side-note, I'm genuinely curious as to how big the Venn Diagram overlap is between those who opposed Scottish independence and those who voted for the Brexit--and vice-versa), and given the specific economic grievances the Scottish National Party held against merry ol' England, I guess I had kinda assumed that Scotland must really suck or something. And perhaps outside the capitol, things are more sketch.

Nevertheless, I was still so unprepared for just how lovely Edinburgh is! The pristine, clean streets, the dazzling diversity of architecture from Medieval to Modernist, the bag-pipers busking on the streets, the Halloween decor simultaneously exported to and imported from the United States (now there's the paradox of post-colonialism in a nutshell!), the lush green trees tinged with autumn leaves--it was rejuvenating, is what it was.

Edingburgh Castle was of course the highlight, and everything else was a cherry on top--but there were still lots of cherries. I was especially enamored with the Sir Walter Scott Memorial; I've seen a number of dead-author's placards by now, but there are Kings and U.S. Presidents with less elaborate monuments than Scott's.

My middle-name is derived from the clan MacLeland, my Dad's Mother's line. As in Denmark, I was again left wondering: does the weather here feel homey cause it reminds me of Washington, or is it the other way around?

[View from Edinburgh Castle]

Thursday, October 13, 2016

On Bob Dylan and John Ashbery

So one of the predominant responses I'm noticing to Bob Dylan's Nobel for Lit. is (generally unfavorable) comparisons to John Ashbery, of all people, e.g. "Look, Dylan's fine, but he's no Ashbery" or "So when does Ashbery win a Grammy?" and etc. Implicit in these responses is the argument that Dylan, as a song-writer, is not a poet, that he writes in a completely different genre.

However, though I'm sympathetic, this argument is complicated by the fact that Ashbery himself blurs the lines between genres; for example, his 1972 work "Three Poems" is a collection of extended, book-length prose meditations--"prose-poems" we now call 'em, but usually folks just call them essays. In fact, I'm willing to bet a number of critics would still dispute whether they should be called "Poems," so much do they resemble straight-prose.

But that's exactly the nomenclature that Ashbery is questioning with the title "Three Poems": can any text be read as a poem as long we label it as such? How does genre influence our engagement with a text? Why *can't* song-lyrics be read as poetry? Was not ancient epic poetry sung? Was not Beowulf? How do we even define "poetry"? We are a long, long way out from meters and rhyme-schemes.

Don't get me wrong, I still think Bob Dylan's Nobel is kinda silly: the

man certainly doesn't lack for recognition, and I generally prefer the

Nobel goes to folks who do (e.g. as happened with Samuel Beckett and

William Faulkner). Nevertheless, Ashbery deeply complicates these

questions, not clarifies them.

Also, this comes only 8 years after the Nobel Lit. committee announced that there were no plans to award an American in the near future, considering out literature to be too "provincial". The pull of Boomer nostalgia crosses national partisanship, I suppose.

Also, this comes only 8 years after the Nobel Lit. committee announced that there were no plans to award an American in the near future, considering out literature to be too "provincial". The pull of Boomer nostalgia crosses national partisanship, I suppose.

A Defense of "Rockism" So-Called

Nowadays, to be labeled a "Rockist" is a borderline slur: music critics lob it at each to slander their opponent as snobbish, stagnant, out-of-date and out-of-touch. Among certain cultural critics, it is practically synonymous with "racist," inasmuch as "Rockists" supposedly only prefer music gate-kept by an overwhelmingly-white establishment of elderly men. A part of me is sympathetic to these anti-"Rockist" screeds, for indeed a myopic insistence on a single, aging genre can indeed cut one off from so much other excellent music--especially from minorities, which our country has a long, atrocious history of silencing.

Yet like all sweeping terms, there are significant problems with "Rockist". First is the fact that the biggest, most unapologetic "Rockists" I have ever met are Hispanic. It is the young Mexican-American men I've known who are the biggest fans of, say, Soundgarden, of Metallica, the White Stripes, the Strokes, who claim that Radiohead peaked with The Bends. Given how much of Rock 'n Roll was influenced by Ricky Valens, Carlos Santana, ? and the Mysterions, Rage Against the Machine, and even At The Drive-In, this shouldn't surprise us. To stereotype "Rockists" as exclusively white is itself rather racist.

It's also classist: Coastal elites and suburbanites may have long ago moved on from Rock 'n Roll, but, having lived in the Midwest, I can assure you that most the middle of the country has most certainly not. And lest one dismiss that all as "Flyover" country conservatism, let us remember that Rock was first and foremost a Working Class genre, the music of the anti-elites. From Chuck Berry singing "Johnny B. Goode" to Little Richard out of Jim Crow Georgia; from Alan Freed broadcasting across rust-belt Cleveland to Elvis Presley emerging from Memphis, Tennessee; from the Beatles out of the Liverpool docks to Bob Dylan hitch-hiking from northern Minnesota; from Bruce Springsteen escaping the failing-factories of New Jersey to the Ramones trapped in Queens; from Black Sabbath in the Birmingham steel mills to Guns 'n Roses running from Indiana to L.A.; from Jimi Hendrix out of rained-out Seattle to Kurt Cobain on the muddy banks of the Wishkah; from The Stooges' Forgotten Boy to The Replacements' Bastards of Young; from U2 in bombed-out Ireland to the White Stripes hailing from dying Detroit, and etc., etc., etc.--Rock 'n Roll has most often been identified with the Working Classes. Even when so many of these bands are of Middle-Class or even Upper-Class extraction (as with, say, Led Zeppelin or Queen), their most faithful audiences nevertheless remain found in the lower income tax brackets that dominate the middle of the country.

Which makes sense, given that these "Rockists" are often folks from hard-labor backgrounds who work all day with the power-tools of heavy-machinery, and then work all night with the power-tools of amplifiers and guitar-distortion--all in a quest to reclaim their humanity from a dehumanizing industry. It is no mystery to me why so many Hispanics are "Rockists" so-called--they above all are still entangled directly with physical labor, struggling to survive in an exploitative market system. We can map the rise and fall of Rock's fortunes with the rise and fall of the Working Classes' fortunes, as America has shifted from a Manufacturing to a Service economy.

This crucial shift may help explain that most petulant of "Rockist" boasts, "At least we play our own instruments!!" Now I will be the first insist that whether one plays or programs ones music is completely irrelevant to whether or not the music is beautiful; nevertheless, one can understand where a "Rockist" Working Class is coming from, how threatened they would feel to behold their skills and livelihoods rendered largely irrelevant by computerized machinery--as has already happened to the American Working Class at large. For the sad fact of the matter is that U.S. Manufacturing is not on the decline, in fact that sector has never been more robust--but the jobs no longer exist because it's all automated now. Foreigners didn't kill the factory jobs, computers did--and so the Working Class is naturally resentful of computers.

Likewise, with the rise of the DJ, human beings are rendered irrelevant to the production of music--just as human beings are rapidly rendered irrelevant to production generally. Even Hip-Hop at least requires a human voice; EDM requires no human presence whatsoever. One can easily imagine a computer algorithm programmed to write all our dance music for us, eliminating human input entirely. The dancers on the floor become subject solely to the whims of the machines, like some dystopic Matrix-cum-Terminator nightmare, wherein the vast majority of world is rendered superfluous, disposable, excess population. It's not just Rock 'n Roll we worry about disappearing, but the human race entirely.

These are real concerns; the Working Class is indeed being left behind, as the majority of the jobs created in our sluggish economic recovery have occurred in the cities, and that primarily within service economies, while the Rust Belt and rural-areas are forgotten--where, not coincidentally, drug-use and suicides are soaring. If ever you were baffled by the rise of Bernie Sanders and (much more alarmingly) Donald Trump, know that they have little to do with the rise of free-loaders or racists respectively, but the reaction of a working class lashing out. It is telling to me that the most vicious thing Bruce Springsteen could think to call Trump was "a con man"--of working class origins himself, Springsteen fully understands the blind rage that drives so many of the working poor to Trump. Springsteen only objects to how that anger is hijacked by a rich sleaze-bag, not as to whether its justified in the first place. No matter what else happens in November, as long as this country continues to ignore the poor like we do, then all those potential-Trump voters will still be there--as will the Bernie Sanders voters. And though those two groups may hold vastly antithetical ideas for how to fix America, one thing remains for sure: both groups will remain pissed. And nothing fuels Rock more than anger.

Yet like all sweeping terms, there are significant problems with "Rockist". First is the fact that the biggest, most unapologetic "Rockists" I have ever met are Hispanic. It is the young Mexican-American men I've known who are the biggest fans of, say, Soundgarden, of Metallica, the White Stripes, the Strokes, who claim that Radiohead peaked with The Bends. Given how much of Rock 'n Roll was influenced by Ricky Valens, Carlos Santana, ? and the Mysterions, Rage Against the Machine, and even At The Drive-In, this shouldn't surprise us. To stereotype "Rockists" as exclusively white is itself rather racist.

It's also classist: Coastal elites and suburbanites may have long ago moved on from Rock 'n Roll, but, having lived in the Midwest, I can assure you that most the middle of the country has most certainly not. And lest one dismiss that all as "Flyover" country conservatism, let us remember that Rock was first and foremost a Working Class genre, the music of the anti-elites. From Chuck Berry singing "Johnny B. Goode" to Little Richard out of Jim Crow Georgia; from Alan Freed broadcasting across rust-belt Cleveland to Elvis Presley emerging from Memphis, Tennessee; from the Beatles out of the Liverpool docks to Bob Dylan hitch-hiking from northern Minnesota; from Bruce Springsteen escaping the failing-factories of New Jersey to the Ramones trapped in Queens; from Black Sabbath in the Birmingham steel mills to Guns 'n Roses running from Indiana to L.A.; from Jimi Hendrix out of rained-out Seattle to Kurt Cobain on the muddy banks of the Wishkah; from The Stooges' Forgotten Boy to The Replacements' Bastards of Young; from U2 in bombed-out Ireland to the White Stripes hailing from dying Detroit, and etc., etc., etc.--Rock 'n Roll has most often been identified with the Working Classes. Even when so many of these bands are of Middle-Class or even Upper-Class extraction (as with, say, Led Zeppelin or Queen), their most faithful audiences nevertheless remain found in the lower income tax brackets that dominate the middle of the country.

Which makes sense, given that these "Rockists" are often folks from hard-labor backgrounds who work all day with the power-tools of heavy-machinery, and then work all night with the power-tools of amplifiers and guitar-distortion--all in a quest to reclaim their humanity from a dehumanizing industry. It is no mystery to me why so many Hispanics are "Rockists" so-called--they above all are still entangled directly with physical labor, struggling to survive in an exploitative market system. We can map the rise and fall of Rock's fortunes with the rise and fall of the Working Classes' fortunes, as America has shifted from a Manufacturing to a Service economy.

This crucial shift may help explain that most petulant of "Rockist" boasts, "At least we play our own instruments!!" Now I will be the first insist that whether one plays or programs ones music is completely irrelevant to whether or not the music is beautiful; nevertheless, one can understand where a "Rockist" Working Class is coming from, how threatened they would feel to behold their skills and livelihoods rendered largely irrelevant by computerized machinery--as has already happened to the American Working Class at large. For the sad fact of the matter is that U.S. Manufacturing is not on the decline, in fact that sector has never been more robust--but the jobs no longer exist because it's all automated now. Foreigners didn't kill the factory jobs, computers did--and so the Working Class is naturally resentful of computers.

Likewise, with the rise of the DJ, human beings are rendered irrelevant to the production of music--just as human beings are rapidly rendered irrelevant to production generally. Even Hip-Hop at least requires a human voice; EDM requires no human presence whatsoever. One can easily imagine a computer algorithm programmed to write all our dance music for us, eliminating human input entirely. The dancers on the floor become subject solely to the whims of the machines, like some dystopic Matrix-cum-Terminator nightmare, wherein the vast majority of world is rendered superfluous, disposable, excess population. It's not just Rock 'n Roll we worry about disappearing, but the human race entirely.

These are real concerns; the Working Class is indeed being left behind, as the majority of the jobs created in our sluggish economic recovery have occurred in the cities, and that primarily within service economies, while the Rust Belt and rural-areas are forgotten--where, not coincidentally, drug-use and suicides are soaring. If ever you were baffled by the rise of Bernie Sanders and (much more alarmingly) Donald Trump, know that they have little to do with the rise of free-loaders or racists respectively, but the reaction of a working class lashing out. It is telling to me that the most vicious thing Bruce Springsteen could think to call Trump was "a con man"--of working class origins himself, Springsteen fully understands the blind rage that drives so many of the working poor to Trump. Springsteen only objects to how that anger is hijacked by a rich sleaze-bag, not as to whether its justified in the first place. No matter what else happens in November, as long as this country continues to ignore the poor like we do, then all those potential-Trump voters will still be there--as will the Bernie Sanders voters. And though those two groups may hold vastly antithetical ideas for how to fix America, one thing remains for sure: both groups will remain pissed. And nothing fuels Rock more than anger.

Monday, October 10, 2016

Once Upon a Halloween in China

My one twinge of regret when I flew to China Autumn of '06 was that, for the first time ever, I would completely miss Halloween (even Puerto Rico has trick-or-treaters nowadays). Little did I know that I was about to have the most intensive Halloween of my life. For the private school I taught at wasn't just content to teach English with genuine American instructors, no--this place was all about cultural immerson, and as everyone worth their salt knew, that meant that these middle-schoolers were going to celebrate Halloween, dangnabit!

As such, Ken and I threw together a slap-dash, super-simple ppt. ("In this slide we see American children in scaaaaary costumes! And in this one we see a haaaaunted house... And in this one we see...candy!--no, no, you can't have any, that's just a slide on a screen"). We presented it over 20 times to over 20 different sections. The whole shebang was only about 20 minutes long, followed by the first 20 minutes of Monster House on a pirated DVD, and then class ended. While Ken gave the lecture, I carved a Jack-O-Lantern in the background, for the childrens' assignment was to carve a pumpkin of their own by October 31st, and I was showing them how.

That is, from fearing I wouldn't get to carve a single lantern that year, I carved more in one week than I had in near my entire life.

And with what factory-efficiency did I mass-produce those Jack-O-Lanterns! It was probably the most American thing I did in China, for better and for worse. A quick kitchen-knife around the stem, scrapping out the guts with brute strength, then stabbing out 3 triangles and a mouth. There was neither care nor craftsmanship, only a need to crank out as much product as fast as possible. My pride was not in my skill, but in my speed. The U.S. work-ethic in a nut-shell, ladies and gents!

So imagine my astonishment when those Chinese children, who had only learned about Halloween the week before, not only carved Jack-O-Lanterns, but carved (doubtless with the aid of their parents and their fine-carpentry sets) some of the most exquisitely detailed pumpkins I have ever seen in my life! Flying dragons, elegant calligraphy, portraits of old Confucians with their every wrinkle subtlety traced into the skin--and all this for pumpkins that would rot in a week! To my shame did I fail to take pictures of them. Yes, it is in the land of sweat-shops and cheap-production, of all places, that the tradition of careful-craftsmanship and beauty-for-its-own-sake still lives!

Halloween night proper, Ken and I finally finished watching Monster House (you can only watch the first 20 minutes so many times before you are filled with an irrational need to witness the ending) and placed a lit Jack-O-Lantern outside. The next morning Ken got up early for a jog, only to find that someone had turned its face around--superstition still lives in the Middle Kingdom, too. Ken turned the face back around and then went running. When he returned, he found the pumpkin on the ground, smashed to pieces.

As such, Ken and I threw together a slap-dash, super-simple ppt. ("In this slide we see American children in scaaaaary costumes! And in this one we see a haaaaunted house... And in this one we see...candy!--no, no, you can't have any, that's just a slide on a screen"). We presented it over 20 times to over 20 different sections. The whole shebang was only about 20 minutes long, followed by the first 20 minutes of Monster House on a pirated DVD, and then class ended. While Ken gave the lecture, I carved a Jack-O-Lantern in the background, for the childrens' assignment was to carve a pumpkin of their own by October 31st, and I was showing them how.

That is, from fearing I wouldn't get to carve a single lantern that year, I carved more in one week than I had in near my entire life.

And with what factory-efficiency did I mass-produce those Jack-O-Lanterns! It was probably the most American thing I did in China, for better and for worse. A quick kitchen-knife around the stem, scrapping out the guts with brute strength, then stabbing out 3 triangles and a mouth. There was neither care nor craftsmanship, only a need to crank out as much product as fast as possible. My pride was not in my skill, but in my speed. The U.S. work-ethic in a nut-shell, ladies and gents!

So imagine my astonishment when those Chinese children, who had only learned about Halloween the week before, not only carved Jack-O-Lanterns, but carved (doubtless with the aid of their parents and their fine-carpentry sets) some of the most exquisitely detailed pumpkins I have ever seen in my life! Flying dragons, elegant calligraphy, portraits of old Confucians with their every wrinkle subtlety traced into the skin--and all this for pumpkins that would rot in a week! To my shame did I fail to take pictures of them. Yes, it is in the land of sweat-shops and cheap-production, of all places, that the tradition of careful-craftsmanship and beauty-for-its-own-sake still lives!

Halloween night proper, Ken and I finally finished watching Monster House (you can only watch the first 20 minutes so many times before you are filled with an irrational need to witness the ending) and placed a lit Jack-O-Lantern outside. The next morning Ken got up early for a jog, only to find that someone had turned its face around--superstition still lives in the Middle Kingdom, too. Ken turned the face back around and then went running. When he returned, he found the pumpkin on the ground, smashed to pieces.

Sunday, September 25, 2016

China A Decade Later

My wife is a flight-attendant, and this weekend she worked a trip to Shanghai. This has put me in a deeply reflective mood, because it was exactly a decade and a month ago that I first walked the streets of Shanghai myself. At the time I was a junior in college, off-track at BYU-Idaho, and my chief goal at the time was to get as far away from Rexburg as I possibly could--and boy did I succeed!

Late August of '06, I flew from San Francisco to Shanghai all alone, a wannabe-English major with only an Associates and no formal teacher training to boot, sent by a fledgling Idaho-based outfit called China Horizons--years later, the founder Jacob Harlan even apologized for flying me over all by my lonesome self; the company has since vastly expanded, and now does a much more admirable job of sending whole groups over together, such that their various teachers travel with a mutual support system already in place. In those early days, however, I was quite solitary. Not only was I flying solo into one of the largest cities on earth, but from Shanghai I had to figure out how to take a 12-hour train-ride west to AnHui Province, to teach at a private middle-school in the "small" town of AnQing (pop. 600,000). If ever anything was the opposite of insular, barely-populated, middle-of-nowhere Rexburg, it was The Middle Kingdom: China.

But of course my Chinese adventure was about more than just escaping the oppressive smallness of Rexburg. At the time I had been home from my mission to Puerto Rico for 2 solid years--and at that halcyon age, being home from your mission for as long as you were out is a sobering moment, a realization that every missionary you could have possibly known is home now, that the institutional memory of your very existence there has already been erased, that you either live on in the hearts of a few scattered Puerto Ricans or nowhere at all. The mission was no longer a thing I had recently done, had "just gotten home from".

In short, I needed a new adventure, something to reassure myself that my life hadn't already peaked at 21, that I wouldn't remain mired in memory, re-hashing half-remembered "glory days" forever, that there was still so much to look forward to. What's more, I had to know that I was capable of doing such things--which was by no means a given for me at the time. I was kinda shy and awkward growing up (in other words, I was a teenager), and frankly a bit of an unambitious home-body, yearning for something more yet still too trepidous to take any real risks. Yes, I had risen to the challenge of a Caribbean mission at the tender age of 19--and grateful that I had--but that whole experience was still mostly financed and encouraged by family and Church, it was an expected thing that I should do.

My sudden decision to go to China, then, was perhaps the first adult decision I made entirely on my own, took the initiative on my own, paid for on my own, accepted the risks of on my own. And the risks were real--I even had a mini-panic attack on the flight over the Pacific, as I realized that I didn't know Chinese, I knew no one in China, that I scarcely had cash in my bank account. "Turn this plane around!" I wanted to scream, "I'm going to die out there!"

Fortunately I was sitting next to a retired newspaper reporter who was returning to China for the 6th time to teach English himself, and he quickly reassured me of how kind and friendly and hospitable the Chinese are (which proved to be true), gave me some advice, some pointers, some encouragement, even complimented me for being so daring at such a young age. I don't remember his name and I doubt he remembers me (if he's still alive...), but I would love to thank him again--he sure did help me get off to China on the right foot.

In the years since my semester in China, I've roamed fairly widely, enough to consider myself a reasonably confident, seasoned traveler (if I do say so myself), one who is no longer intimidated by foreign customs and unknown tongues. (I'm also a much more experienced and confident teacher, while we're at it). International travel now feels familiar to me.

But then, everything feels familiar after China--when you are an American abroad, you can't get much more jumping-in-the-deep-end than the People's Republic. The scorpions on a stick, pig-feet, steamed-lilies, and fish and foul with their heads still attached for dinner; the family-names first and given-names last; the baffled way you and they regard each other because they prefer their water hot while you prefer it cold; the opinions kept private and the Tai Chi practiced openly; the collective refusal to remember the '60s; the capitalist communism; the oxen plowing in the shadows of sky-scrapers; the swastika as Buddhist instead of Nazi; the stiff-as-a-board beds; the hole-in-the-floor toilets; the every-which-way they are blunt where you are delicate and delicate where you are blunt; the way even the local Police Chief calls you handsome, and random teenagers want their picture with you; how you will never be quite sure if they are actually inviting you over for dinner or just being polite; their utter lack of personal space yet profound discomfort with actual physical touch; the chaotic order of their every traffic stop, how the mass of pedestrians weave through the oncoming traffic in perfect safety; the language with zero correspondence to the Latin alphabet, that grammatically formalizes the vocal-tones we refuse to admit exist in English too--take every last thing you are used to in America and reverse it. I had to sink or swim, and with a little help from my new friends there--Chinese and American alike--I learned to swim.

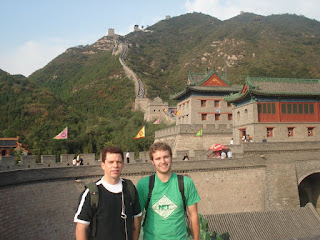

Over all, China was an important turning-point and confidence-booster in my life (and hopefully my students actually learned a thing or two from me also, as I faked my way through teaching them how to pronounce the letters V and L--and I do declare that you haven't lived till you've led a chorus of Chinese 7th graders in belting out "Yellow Submarine" and John Denver's "Country Roads"). And when I finally stood upon the Great Wall one brisk, bright mid-Autumn morning, it dawned on me: I might actually be able to do this whole see-the-world, seize-the-day, live-you-life-while-you're-still-young thing after all (it's probably no accident I married someone who chose to become a flight attendant). While it is sobering to realize a full decade has now passed, it is supremely gratifying--even a relief--to note how full that decade has been.

But though I am now more sure than ever that there is still so much more to come, my wife in Shanghai today has nonetheless got me feeling nostalgic, so indulge me as I post the barest sampling of decade-old photographs:

Late August of '06, I flew from San Francisco to Shanghai all alone, a wannabe-English major with only an Associates and no formal teacher training to boot, sent by a fledgling Idaho-based outfit called China Horizons--years later, the founder Jacob Harlan even apologized for flying me over all by my lonesome self; the company has since vastly expanded, and now does a much more admirable job of sending whole groups over together, such that their various teachers travel with a mutual support system already in place. In those early days, however, I was quite solitary. Not only was I flying solo into one of the largest cities on earth, but from Shanghai I had to figure out how to take a 12-hour train-ride west to AnHui Province, to teach at a private middle-school in the "small" town of AnQing (pop. 600,000). If ever anything was the opposite of insular, barely-populated, middle-of-nowhere Rexburg, it was The Middle Kingdom: China.

But of course my Chinese adventure was about more than just escaping the oppressive smallness of Rexburg. At the time I had been home from my mission to Puerto Rico for 2 solid years--and at that halcyon age, being home from your mission for as long as you were out is a sobering moment, a realization that every missionary you could have possibly known is home now, that the institutional memory of your very existence there has already been erased, that you either live on in the hearts of a few scattered Puerto Ricans or nowhere at all. The mission was no longer a thing I had recently done, had "just gotten home from".

In short, I needed a new adventure, something to reassure myself that my life hadn't already peaked at 21, that I wouldn't remain mired in memory, re-hashing half-remembered "glory days" forever, that there was still so much to look forward to. What's more, I had to know that I was capable of doing such things--which was by no means a given for me at the time. I was kinda shy and awkward growing up (in other words, I was a teenager), and frankly a bit of an unambitious home-body, yearning for something more yet still too trepidous to take any real risks. Yes, I had risen to the challenge of a Caribbean mission at the tender age of 19--and grateful that I had--but that whole experience was still mostly financed and encouraged by family and Church, it was an expected thing that I should do.

My sudden decision to go to China, then, was perhaps the first adult decision I made entirely on my own, took the initiative on my own, paid for on my own, accepted the risks of on my own. And the risks were real--I even had a mini-panic attack on the flight over the Pacific, as I realized that I didn't know Chinese, I knew no one in China, that I scarcely had cash in my bank account. "Turn this plane around!" I wanted to scream, "I'm going to die out there!"

Fortunately I was sitting next to a retired newspaper reporter who was returning to China for the 6th time to teach English himself, and he quickly reassured me of how kind and friendly and hospitable the Chinese are (which proved to be true), gave me some advice, some pointers, some encouragement, even complimented me for being so daring at such a young age. I don't remember his name and I doubt he remembers me (if he's still alive...), but I would love to thank him again--he sure did help me get off to China on the right foot.

In the years since my semester in China, I've roamed fairly widely, enough to consider myself a reasonably confident, seasoned traveler (if I do say so myself), one who is no longer intimidated by foreign customs and unknown tongues. (I'm also a much more experienced and confident teacher, while we're at it). International travel now feels familiar to me.

But then, everything feels familiar after China--when you are an American abroad, you can't get much more jumping-in-the-deep-end than the People's Republic. The scorpions on a stick, pig-feet, steamed-lilies, and fish and foul with their heads still attached for dinner; the family-names first and given-names last; the baffled way you and they regard each other because they prefer their water hot while you prefer it cold; the opinions kept private and the Tai Chi practiced openly; the collective refusal to remember the '60s; the capitalist communism; the oxen plowing in the shadows of sky-scrapers; the swastika as Buddhist instead of Nazi; the stiff-as-a-board beds; the hole-in-the-floor toilets; the every-which-way they are blunt where you are delicate and delicate where you are blunt; the way even the local Police Chief calls you handsome, and random teenagers want their picture with you; how you will never be quite sure if they are actually inviting you over for dinner or just being polite; their utter lack of personal space yet profound discomfort with actual physical touch; the chaotic order of their every traffic stop, how the mass of pedestrians weave through the oncoming traffic in perfect safety; the language with zero correspondence to the Latin alphabet, that grammatically formalizes the vocal-tones we refuse to admit exist in English too--take every last thing you are used to in America and reverse it. I had to sink or swim, and with a little help from my new friends there--Chinese and American alike--I learned to swim.

Over all, China was an important turning-point and confidence-booster in my life (and hopefully my students actually learned a thing or two from me also, as I faked my way through teaching them how to pronounce the letters V and L--and I do declare that you haven't lived till you've led a chorus of Chinese 7th graders in belting out "Yellow Submarine" and John Denver's "Country Roads"). And when I finally stood upon the Great Wall one brisk, bright mid-Autumn morning, it dawned on me: I might actually be able to do this whole see-the-world, seize-the-day, live-you-life-while-you're-still-young thing after all (it's probably no accident I married someone who chose to become a flight attendant). While it is sobering to realize a full decade has now passed, it is supremely gratifying--even a relief--to note how full that decade has been.

But though I am now more sure than ever that there is still so much more to come, my wife in Shanghai today has nonetheless got me feeling nostalgic, so indulge me as I post the barest sampling of decade-old photographs:

The Jade Buddhist Temple in downtown Shanghai.

The very modern view from this very ancient temple.

The Oriental Pearl Tower in Shanghai.

The Great Wall of China in Beijing

At the Great Wall with my American roommate/co-worker/friend Ken Carlston.

I had, and continue to have, no idea who any of these people were.

Entrance to the Forbidden City.

Mishaps at a Chinese masseuse parlor.

At Guniu national forest.

This pic is one inspirational quote away from a Dental Office.

Hiking Tianzhu Shan.

That chicken had been alive only an hour earlier.

A mere sliver of the view from atop Yellow Mountain.

Me taking in said overwhelming-view that no camera will ever be able to capture.

That bridge, for scale.

The sacred Buddhist mountain Jiuhua Shan.

Thursday, September 15, 2016

The Catcher in the Rye Revisited; or, Catcher in the Rye as a Christmas Novel

When I was a teenager I read The Catcher in the Rye. I also read Catch-22, Tropic of Cancer, Dilbert comics, wore Chuck Taylors, and listened to The Doors, Queen's Greatest Hits, and Dark Side of the Moon. I wasn't exactly original. (Teenagers never are).

But maybe originality is overrated--not to mention a myth--and the reason why J.D. Salinger's lone novel continues to sell in excess of 250,000 copies a year well over a half-century after its publication is because there is nothing original about its premise: a teenager hates his life. Holden Caulfield's is the common voice of adolescent dissatisfaction, distilled down to its purest and most impotent rage. Sometimes you don't need to read something original--sometimes you just need to know you're not alone, that there's someone else out there who understands.

Or Holden Caulfield is just a total spoiled brat, an epitome of unexamined privilege so devoid of real problems that he has to invent some to justify his narcissism, selfishness, and general dickishness. Such, increasingly, has been the summation of a growing number of folks, in the surprisingly burgeoning sub-genre of Catcher in the Rye re-reads.

These various responses, in fact, had me a tad trepidous to re-read Catcher myself. Even after Salinger's death in 2011, I couldn't quite bring myself to revisit Holden. Some cherished childhood memories are best left in the past, I figured.

But then last week at the airport, disaster struck: I lost the book I was reading (Vol. 4 of In Search of Lost Time--and boy, if there could ever be two more differing approaches towards remembering childhood than Proust and Salinger!). Begrudgingly, like an amateur, I sauntered over to the Airport Bookstore & Minimart to find a replacement. Amidst all those paint-by-numbers spy thrillers, hackneyed romances, formulaic fantasies, flavor-of-the-week best-sellers, cash-grab celebrity bios, petulant political screeds, insipid self-help books, and insidious Get-Rich-Quick schemes, I felt a sort of nausea fill the pit of my stomach.

That is, I was put in just the right mindset to re-read Catcher...which is why it startled me to find the book on the shelf! What strange company for Caulfield to be keeping! How ironic to be so surrounded by "such a bunch of phonies," as Holden might say! It almost felt like some secret joke perpetrated by an irate bookstore employee. I couldn't resist--I bought a copy. Just finished it this afternoon.

Let's get something out of the way first: Holden Caulfield is indeed insufferable. His critics are right. But what his critics miss is that he is insufferable in the exact same way all teenagers are insufferable. That is an incredibly rare feet--in most film, TV, and fiction, teenagers are idealized, articulate, a fantasy of what we liked to imagine we were like at that age, rather than a reflection of what we were actually like. Ferris Bueller is who we wanted to be; but Holden Caulfield is who we actually were. I suspect that much of the adult backlash against Holden is sheer resentment, for reminding us of how embarrassing we all sounded in our teens, which we've spent most our adulthood trying to forget.

But here's the other thing about Holden: he's also self-aware! Multiple times throughout the novel, Holden mentions how he himself is a phony, duplicitous, inconsistent, and terrible. Pay attention for those moments if you choose to re-read it. Indeed, I dare say that a huge source of Holden's frustration and anger is his growing awareness--which, as a true teenager, he still lacks the vocabulary to fully express--that he is in fact inextricably complicit with the phoniness of the world!

And that I think is why the novel continues to resonate even today: because we all feel that same rage at our own inescapable complicity. Our clothing is sewn by children in third-world sweatshops; our food harvested by exploited immigrant labor; our rubber comes from African and Malaysian slave plantations; our electronics from nightmarish Tawainese factories, built with rare-earth minerals mined by Afghan child slaves; our diamonds from genocidal warlords; our gasoline from hyper-destructive industries; our high standard of living from ruthless corporations; and so on and so forth. In America, we are all spoiled, petulant, narcissistic brats, people who burn away all our many opportunities and invent problems to justify our misery--Holden, at least, is aware that he does so. He is also one of the few characters in fiction who actively tries to disavow all his unearned privilege--and even fails as he tries. The problem of privilege runs deep.

But then, his anger is not solely rooted in societal injustice, is it; early in the novel, we learn his brother Allie had recently died of leukemia. Holden's grief, then, is of a kind with Prince Hamlet's--they are both morose, brooding jerks precisely because they are both grieving. Grief has a funny way of stripping away our filters, dropping our defenses, making nothing feel like it matters anymore. Holden isn't just the archetype for the raging teenager; he is also that of the grieving brother.

Nor do I bring up Hamlet arbitrarily (well, besides their shared spaces on every High School syllabi ever); a couple years ago I argued that Hamlet can be read as a Christmas play. Remember that the latter takes place in the winter months; the ghost appears "against that season...Wherein our Saviour's birth is celebrated;" and that for centuries, the telling of ghost stories was a holiday tradition. As I pointed out back then, it is no coincidence that Dicken's A Christmas Carol is first and foremost a ghost story, that Joyce's "The Dead" takes place at a Christmas party, that Andy Williams' 1963 hit "It's the Most Wonderful Time of the Year" boasts "There'll be scary ghost stories..." Up till two short generations ago, the dead were as much a part of Christmas as the trees and mistletoe.

And like Shakespeare's Hamlet, Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye (and I suspect this point isn't emphasized nearly enough) can also be read as a Christmas novel. It, too, takes place in late December; Holden gets depressed at one point when he sees some men swearing as they put up a municipal Christmas Tree; his younger sister Phoebe is playing the lead in a Christmas pageant; she lends Holden some of her gift-buying money; and as had happened for centuries of Christmases, a ghost haunts the proceedings, that of the late Allie Caulfield.

I perhaps read The Catcher in the Rye a little too early in the season--it is really a Christmas story. More precisely, it is a Christmas ghost story, in the same tradition as Dickens, Joyce, and Shakespeare. Though a self-proclaimed "kind of an atheist," Holden nevertheless possesses Christ's same absolute impatience for "phonies"--or as the Savior put it, "Scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites!" (Matt. 23:13). The novel's title even comes from Holden's dream of catching kids-at-play from falling off a cliff--that is, Holden wishes to be a savior to little children, "for of such is the kingdom of God." Despite all its casual blasphemy, this text is permeated with desire for a Christ.

I may need to add Catcher to the thin list of books I re-read every Christmas, the books that actually remind me of the "reason for the season"--namely, that because we are all, like Holden, such prodigal sons, because we are all selfish, wasteful, despicable phonies (and that never more so than during Christmas), we are all in need of a Savior more desperately than ever.

But maybe originality is overrated--not to mention a myth--and the reason why J.D. Salinger's lone novel continues to sell in excess of 250,000 copies a year well over a half-century after its publication is because there is nothing original about its premise: a teenager hates his life. Holden Caulfield's is the common voice of adolescent dissatisfaction, distilled down to its purest and most impotent rage. Sometimes you don't need to read something original--sometimes you just need to know you're not alone, that there's someone else out there who understands.

Or Holden Caulfield is just a total spoiled brat, an epitome of unexamined privilege so devoid of real problems that he has to invent some to justify his narcissism, selfishness, and general dickishness. Such, increasingly, has been the summation of a growing number of folks, in the surprisingly burgeoning sub-genre of Catcher in the Rye re-reads.

These various responses, in fact, had me a tad trepidous to re-read Catcher myself. Even after Salinger's death in 2011, I couldn't quite bring myself to revisit Holden. Some cherished childhood memories are best left in the past, I figured.

But then last week at the airport, disaster struck: I lost the book I was reading (Vol. 4 of In Search of Lost Time--and boy, if there could ever be two more differing approaches towards remembering childhood than Proust and Salinger!). Begrudgingly, like an amateur, I sauntered over to the Airport Bookstore & Minimart to find a replacement. Amidst all those paint-by-numbers spy thrillers, hackneyed romances, formulaic fantasies, flavor-of-the-week best-sellers, cash-grab celebrity bios, petulant political screeds, insipid self-help books, and insidious Get-Rich-Quick schemes, I felt a sort of nausea fill the pit of my stomach.

That is, I was put in just the right mindset to re-read Catcher...which is why it startled me to find the book on the shelf! What strange company for Caulfield to be keeping! How ironic to be so surrounded by "such a bunch of phonies," as Holden might say! It almost felt like some secret joke perpetrated by an irate bookstore employee. I couldn't resist--I bought a copy. Just finished it this afternoon.

Let's get something out of the way first: Holden Caulfield is indeed insufferable. His critics are right. But what his critics miss is that he is insufferable in the exact same way all teenagers are insufferable. That is an incredibly rare feet--in most film, TV, and fiction, teenagers are idealized, articulate, a fantasy of what we liked to imagine we were like at that age, rather than a reflection of what we were actually like. Ferris Bueller is who we wanted to be; but Holden Caulfield is who we actually were. I suspect that much of the adult backlash against Holden is sheer resentment, for reminding us of how embarrassing we all sounded in our teens, which we've spent most our adulthood trying to forget.

But here's the other thing about Holden: he's also self-aware! Multiple times throughout the novel, Holden mentions how he himself is a phony, duplicitous, inconsistent, and terrible. Pay attention for those moments if you choose to re-read it. Indeed, I dare say that a huge source of Holden's frustration and anger is his growing awareness--which, as a true teenager, he still lacks the vocabulary to fully express--that he is in fact inextricably complicit with the phoniness of the world!

And that I think is why the novel continues to resonate even today: because we all feel that same rage at our own inescapable complicity. Our clothing is sewn by children in third-world sweatshops; our food harvested by exploited immigrant labor; our rubber comes from African and Malaysian slave plantations; our electronics from nightmarish Tawainese factories, built with rare-earth minerals mined by Afghan child slaves; our diamonds from genocidal warlords; our gasoline from hyper-destructive industries; our high standard of living from ruthless corporations; and so on and so forth. In America, we are all spoiled, petulant, narcissistic brats, people who burn away all our many opportunities and invent problems to justify our misery--Holden, at least, is aware that he does so. He is also one of the few characters in fiction who actively tries to disavow all his unearned privilege--and even fails as he tries. The problem of privilege runs deep.

But then, his anger is not solely rooted in societal injustice, is it; early in the novel, we learn his brother Allie had recently died of leukemia. Holden's grief, then, is of a kind with Prince Hamlet's--they are both morose, brooding jerks precisely because they are both grieving. Grief has a funny way of stripping away our filters, dropping our defenses, making nothing feel like it matters anymore. Holden isn't just the archetype for the raging teenager; he is also that of the grieving brother.

Nor do I bring up Hamlet arbitrarily (well, besides their shared spaces on every High School syllabi ever); a couple years ago I argued that Hamlet can be read as a Christmas play. Remember that the latter takes place in the winter months; the ghost appears "against that season...Wherein our Saviour's birth is celebrated;" and that for centuries, the telling of ghost stories was a holiday tradition. As I pointed out back then, it is no coincidence that Dicken's A Christmas Carol is first and foremost a ghost story, that Joyce's "The Dead" takes place at a Christmas party, that Andy Williams' 1963 hit "It's the Most Wonderful Time of the Year" boasts "There'll be scary ghost stories..." Up till two short generations ago, the dead were as much a part of Christmas as the trees and mistletoe.

And like Shakespeare's Hamlet, Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye (and I suspect this point isn't emphasized nearly enough) can also be read as a Christmas novel. It, too, takes place in late December; Holden gets depressed at one point when he sees some men swearing as they put up a municipal Christmas Tree; his younger sister Phoebe is playing the lead in a Christmas pageant; she lends Holden some of her gift-buying money; and as had happened for centuries of Christmases, a ghost haunts the proceedings, that of the late Allie Caulfield.

I perhaps read The Catcher in the Rye a little too early in the season--it is really a Christmas story. More precisely, it is a Christmas ghost story, in the same tradition as Dickens, Joyce, and Shakespeare. Though a self-proclaimed "kind of an atheist," Holden nevertheless possesses Christ's same absolute impatience for "phonies"--or as the Savior put it, "Scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites!" (Matt. 23:13). The novel's title even comes from Holden's dream of catching kids-at-play from falling off a cliff--that is, Holden wishes to be a savior to little children, "for of such is the kingdom of God." Despite all its casual blasphemy, this text is permeated with desire for a Christ.

I may need to add Catcher to the thin list of books I re-read every Christmas, the books that actually remind me of the "reason for the season"--namely, that because we are all, like Holden, such prodigal sons, because we are all selfish, wasteful, despicable phonies (and that never more so than during Christmas), we are all in need of a Savior more desperately than ever.

Sunday, September 11, 2016

Venice, Copenhagan, Rekljavic

Look, I don't want no guff from you--because life is already so capricious and unfair as it is, that on the rare occasions where it is so in your favor, you learn to take the money and run. Hence, when an opportunity arises to go on what is in effect an all-expense-paid round-trip to Venice--especially when you are a broke community college adjunct grad student--then you friggin' take it. Because you are the sort of person who's not supposed to be able to do this; you are supposed to be at the whims of the market, not vice-versa. Flying to Venice thus becomes a form of resistance: politically, economically, even cosmically.

But hark, there is danger! For you may be tempted to be a total hipster about it, and roll your eyes at the Gondolas, sneering that they're all just some overpriced, overrated tourist trap. Protip: Ride the Gondola anyways. And elect to ride the small canals over the Grand Canal, too. Even the most cynical among you won't be able to repress a smile, nor a sense of awe at this romantic place. It is magical on purpose.

For some reason, it wasn't until I was physically walking the streets of Copenhagan that I suddenly realized I was visiting one of the haunts of my Mother. She straight-up skipped her High School graduation, I recalled, to fly across the Atlantic with my Grandparents, to pick up my Uncle Tom from his mission to Denmark. I also have ancestors from this corner of Scandinavia. You will also note that all of these people I just mentioned are now dead. Hence, as I wandered past the Little Mermaid statue, the colorful homes of Nyhavn, the Danish Royal Palace, the Christus, I couldn't help but feel how I was now stepping where they once stepped, seeing what they once saw--the spirits and ghosts fluttered beside me.

I tried to quote Kierkegaard there, but I wasn't feeling existential enough (though it's not like Hans Christian Anderson is terribly cheery, either). I'm from Washington, so the cool climate of Denmark felt especially like home--or is it the reverse?

In Iceland, everything feels primordial: the visible tectonic plates, the geothermal hotsprings, the moss-covered volcanic rock, even the language with letters unused by English since the composition of Beowulf, all make the island feel like a relic from the dawn of time, a vision of a young Earth. The tour-guide may tell you that at a "mere" 18 million years old, the landmass of Iceland is, geologically speaking, an infant--but that is just another way of emphasizing how much older everything is than humanity, how we really are just guests. (Prometheus was filmed here with reason.)

Of course, such a recognition cannot help but make you feel younger, as well--and to take yourself less seriously. Perhaps that is why the Icelanders, despite their general icy Germanic demeanor, were among the nicest and most helpful people I've ever met, especially when they didn't have to, especially when I needed it most (I almost got stranded at their tiny airport at the edge of the world, save for the kind airport employees who bent over backwards to get me rebooked). Iceland tops all those Human Life Indexes most deservedly.

But hark, there is danger! For you may be tempted to be a total hipster about it, and roll your eyes at the Gondolas, sneering that they're all just some overpriced, overrated tourist trap. Protip: Ride the Gondola anyways. And elect to ride the small canals over the Grand Canal, too. Even the most cynical among you won't be able to repress a smile, nor a sense of awe at this romantic place. It is magical on purpose.

For some reason, it wasn't until I was physically walking the streets of Copenhagan that I suddenly realized I was visiting one of the haunts of my Mother. She straight-up skipped her High School graduation, I recalled, to fly across the Atlantic with my Grandparents, to pick up my Uncle Tom from his mission to Denmark. I also have ancestors from this corner of Scandinavia. You will also note that all of these people I just mentioned are now dead. Hence, as I wandered past the Little Mermaid statue, the colorful homes of Nyhavn, the Danish Royal Palace, the Christus, I couldn't help but feel how I was now stepping where they once stepped, seeing what they once saw--the spirits and ghosts fluttered beside me.

I tried to quote Kierkegaard there, but I wasn't feeling existential enough (though it's not like Hans Christian Anderson is terribly cheery, either). I'm from Washington, so the cool climate of Denmark felt especially like home--or is it the reverse?

In Iceland, everything feels primordial: the visible tectonic plates, the geothermal hotsprings, the moss-covered volcanic rock, even the language with letters unused by English since the composition of Beowulf, all make the island feel like a relic from the dawn of time, a vision of a young Earth. The tour-guide may tell you that at a "mere" 18 million years old, the landmass of Iceland is, geologically speaking, an infant--but that is just another way of emphasizing how much older everything is than humanity, how we really are just guests. (Prometheus was filmed here with reason.)

Of course, such a recognition cannot help but make you feel younger, as well--and to take yourself less seriously. Perhaps that is why the Icelanders, despite their general icy Germanic demeanor, were among the nicest and most helpful people I've ever met, especially when they didn't have to, especially when I needed it most (I almost got stranded at their tiny airport at the edge of the world, save for the kind airport employees who bent over backwards to get me rebooked). Iceland tops all those Human Life Indexes most deservedly.

Monday, August 15, 2016

On Baseball, Football, Leisure, the Labor Movement, and U.S. Manufacturing

Last week I participated in that most perennial of American traditions: going to a baseball game with my Dad and brother. We saw the Mariners play in Seattle, as we had so often when I was growing up. The inherent traditionalism of the sport, paired with the intrinsic leisureliness of the spectacle, couldn't help but put me in a reflective mood.

Specifically, about the leisureliness itself of baseball. The sport in fact has its roots in the U.S. Labor movement; "8 hours to work, 8 hours to sleep, and 8 hours to do as we please" was the rallying cry of the first American Unionists (so much less ambitious than their Socialist counterparts in Europe), who were understandably resentful of their 14-hour work days in horrific factory conditions. The factory owners themselves, of course, were less than thrilled with the prospect of 8-hour work days, and claimed to be battling "indolence, loafing, and laziness" among the Lower Classes with their punishing work days.

This rhetoric, in turn, prompted the factory workers to lay claim to "indolence, loafing, and laziness" directly as a form of political resistance, which they expressed by playing baseball--for there is no sport more laid-back than baseball. Most the time, you'll note, the players are simply standing around, or leaning on the railing, casually waiting for things to happen. The most celebrated legends of baseball--e.g. Babe Ruth--are renowned for drinking, smoking, and walking around the bases. Baseball wasn't just lazy, it was proudly so--it was the working man claiming his right to leisure. It is perhaps no accident that baseball rose to its highest prominence in American culture at the same time that the U.S. Labor movement achieved its greatest gains: the 8-hour work week, overtime pay, weekends, paid holidays, minimum wages, workman's comp.

It is perhaps also not accidental that baseball has been displaced by football in the American psyche at the same time that the Working Class has been displaced. U.S. Manufacturing is mostly automated now, where it hasn't actively been in decline; consequently, the U.S. Labor force has moved from a largely manufacturing economy to a service one. This point is integral: for in the days when factories dominated the U.S. landscape, men worked hard labor jobs--thus proving to others and themselves their own strength, virility, and masculinity--and baseball was how they unwound and relaxed on weekends.

But the majority of our jobs are no longer considered "manly"--our labor is now largely sedentary, service-oriented, with little chance to prove our virility, our masculinity. Fight Club, both the novel and the film, rose to prominence in reaction against an "emasculating" economy, as men fought in underground clubs to vent their pent-up frustration; however, it wasn't fight clubs that arose in real life to give us vents, but American Football. The violence, the toughness, the sheer danger of the sport, gave U.S. males an outlet for their aggression that they could no longer find in their careers.

Yet with this key difference: it is largely a vicarious outlet! For by contrast, when one watches baseball, one is being leisurely even as the players on the field are likewise being leisurely! That is, we are all being leisurely together! There is this unspoken camaraderie across social classes at a baseball game, all claiming their leisure time together at once.

But in football, the athletes are all taking the hits for the spectators! The latter may shout and scream and cheer, channeling and venting all their pent-up energy after a dull work-week; but it is the athletes alone who are subject to all that horrendous violence. Football is a sport wherein 40,000 people who need to exercise more watch 22 men who really need a rest. Despite all the face-paints and colorful costumes and DIY signs to the contrary, there is no genuine camaraderie between spectator and participant in football.

Likewise, in baseball, the crowd may cheer at, say, a double-play, or a home-run, but otherwise we are chatting amiably with our neighbors, hanging out with our friends--the game is as much about us as it is about them. But in football, good luck trying to chat casually with anyone! If you're not screaming the whole game through, then you're doing it wrong, for it's never about you, it's always about them.

We are disconnected from the athletes we watch in football: we likewise no longer feel truly connected to our products (made in China), our clothing (made in sweat-shops), our food (harvested by migrant workers); we are a long way removed from our American agricultural and manufacturing past, wherein we could directly and easily trace where all our products come from. Nowadays we have to advertise certain foods as "locally sourced," as though that were some strange, new thing.

The great popularity of baseball among Latinos is perhaps linked to the fact that they still work in physical labor, especially agriculture--they are still fighting for their right to leisure. (This agricultural-labor connection perhaps explains why our most famous baseball film, Field of Dreams, takes place on a farm, in a corn field).

We likewise all feel disconnected from our policy-makers, from our leaders, from the powerful; after slowly undoing the long gains of the Labor movement, CEOs now make hundreds of times more than their workers, far in excess of what they made in the hey-day of Unions (and of baseball). The recent rise of Bernie Sanders and (perversely) Trump likewise signals a deep and general resentment among working Americans, against a power-class that feels completely disconnected from their lived experiences.

We may still cheer on our favorite political parties, as we do our favorite football teams, but we do not feel like we are actually participating with them--in fact, the loudness of our cheers are usually in direct inverse proportion to our actual influence upon the actions on the field (unless you're a Seahawks fan, of course, but that's a topic for a different day). It is perhaps apropos that your average MLB baseball ticket is reasonably affordable to a working man--while only the rich can afford an NFL game.

I will be curious to see if and how football preserves its current cultural dominance, especially as the whole concussion controversy calls into question the violence inherent in football's whole exploitative system--which is in turn a metonym for our whole exploitative economic system. Moreover, that awareness of the violence endemic to our economic system is clearly spreading throughout our increasingly angry working class, at all point of the political spectrum. If current trends continue to boiling point, we may well return to baseball yet.

Specifically, about the leisureliness itself of baseball. The sport in fact has its roots in the U.S. Labor movement; "8 hours to work, 8 hours to sleep, and 8 hours to do as we please" was the rallying cry of the first American Unionists (so much less ambitious than their Socialist counterparts in Europe), who were understandably resentful of their 14-hour work days in horrific factory conditions. The factory owners themselves, of course, were less than thrilled with the prospect of 8-hour work days, and claimed to be battling "indolence, loafing, and laziness" among the Lower Classes with their punishing work days.

This rhetoric, in turn, prompted the factory workers to lay claim to "indolence, loafing, and laziness" directly as a form of political resistance, which they expressed by playing baseball--for there is no sport more laid-back than baseball. Most the time, you'll note, the players are simply standing around, or leaning on the railing, casually waiting for things to happen. The most celebrated legends of baseball--e.g. Babe Ruth--are renowned for drinking, smoking, and walking around the bases. Baseball wasn't just lazy, it was proudly so--it was the working man claiming his right to leisure. It is perhaps no accident that baseball rose to its highest prominence in American culture at the same time that the U.S. Labor movement achieved its greatest gains: the 8-hour work week, overtime pay, weekends, paid holidays, minimum wages, workman's comp.

It is perhaps also not accidental that baseball has been displaced by football in the American psyche at the same time that the Working Class has been displaced. U.S. Manufacturing is mostly automated now, where it hasn't actively been in decline; consequently, the U.S. Labor force has moved from a largely manufacturing economy to a service one. This point is integral: for in the days when factories dominated the U.S. landscape, men worked hard labor jobs--thus proving to others and themselves their own strength, virility, and masculinity--and baseball was how they unwound and relaxed on weekends.

But the majority of our jobs are no longer considered "manly"--our labor is now largely sedentary, service-oriented, with little chance to prove our virility, our masculinity. Fight Club, both the novel and the film, rose to prominence in reaction against an "emasculating" economy, as men fought in underground clubs to vent their pent-up frustration; however, it wasn't fight clubs that arose in real life to give us vents, but American Football. The violence, the toughness, the sheer danger of the sport, gave U.S. males an outlet for their aggression that they could no longer find in their careers.

Yet with this key difference: it is largely a vicarious outlet! For by contrast, when one watches baseball, one is being leisurely even as the players on the field are likewise being leisurely! That is, we are all being leisurely together! There is this unspoken camaraderie across social classes at a baseball game, all claiming their leisure time together at once.