At Swim-Two-Birds, Flann O'Brien [Brian O'Nolan].

This is a book you experience more than you really understand. I must confess: I have a weakness for books like these--utterly digressional, insane, labyrintine in both prose and structure, everywhere and nowhere at once. Decades before Italo Calvino, several stories are started, abandoned, returned to, intertwined around each other, layered on top of each other. Characters rebel against authors--characters of authors who are also characters created by other authors, presumably all the way up to Flann O'Brien--who himself is the pen-name (and therefore the fictional construct) of Brian O'Nolan. Given how O'Nolan always disavowed this book and its "youthful excesses," I think we can safely play with the idea that all of these various rebellions were successful. Given Ireland's historical preoccupations with independence and rebellions, these authorial revolts are thematically apropos. Given that this book debuted the same year as Finnegans Wake, I think it's fair to say that the Irish Modernists were very much obsessed with deconstructing the stories, the linear narratives, that had been used to justify their colonization--as well as constructing elaborate labyrinths to hide themselves away from the colonizer.

El otoño del patriarca [The Autumn of the Patriarch], Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Marquez published his 1975 Dictator Novel in Spain the same year Franco died--where it promptly became a best-seller. In many ways, it is the inverse of Vargas' Dictator Novel, El fiesta del chivo--whereas the latter is awash in historical specificity and precision, the former is dreamlike, meandering, wandering, featuring a fictional unnamed dictator of some fictional unnamed Caribbean island that is nevertheless a composite of many horrible, brutally real Latin-American dictators. Large swaths of this novel are told in sentences that go on for 20 pages at a time--the sentences never seems to end the same way that death sentences from the General never seem to end--like his reign never seems to end--like time itself never seems to end. But end it all inevitably does: in fact, the novel opens with the vultures creeping into the palace, alerting the populace that the dictator they all so feared really is dead, that they might at last enter the palace with impunity. The General had seemed to control time himself, from the holidays to the clocks to the movements of the trash around the island. Time, however, stays in control throughout, particularly as the General's mother ages.

Heavy oedipal overtones feature in this novel, from the General's unhealthy obsession with his poor mother who herself prays for her son's overthrow, to the peoples' own patricidal fear of the Patriarch (a key word-choice on Marquez's part). This is the labyrinth you can't escape, as opposed to the Irish labyrinth you use to escape.

A Long, Long Way, Sebastian Barry.

In Vargas' 2010 novel Dream of the Celt, Roger Casement tries to convince Irish volunteers to the British army during WWI to defect to Germany; in this 2005 novel, Sebastian Barry explores more in depth the world of these Irish soldiers themselves. Among their many paradoxes: those from southern Ireland thought they really were fighting for Irish Homerule in exchange for their faithful service, while those from Ulster thought they were fighting for the inverse. Most of the novel takes place in the trenches--it's a sort of latter-day All Quiet on the Western Front--with only a couple quick Leaves granted back to Dublin, where protagonist Willie Dunne learns of the Easter Uprising. A stray moment of sympathy for a murdered Republican ruins his relationship with his ardently Unionist father. Almost a work of prose-poetry, the novel loses the Irish within the labyrinth of the trenches, of political firestorms, and literal ones too. It ends about as depressingly as you'd expect.

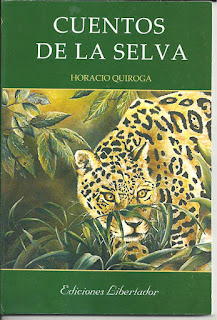

Cuentos de la selva [Jungle Tales], Horacio Quiroga.

This 1918 children's book, featuring short stories about anthropomorphized wildlife interacting with human settlers amidst the steady modernization of Uruguay and Argentina, is basically a South American version of Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book, only without any sort of anchor-character like Mowgli, a slightly more eco-aware sensibility, and with slightly less troubling imperialist overtones. An early example of the labyrinth of the jungle prevalent in 20th century Latin-American literature.

(Below are other books on my reading list that I had already read multiple times before this summer began).

Dubliners, James Joyce.

The groundbreaking 1914 short-story collection about the stories we tell ourselves.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce.

The groundbreaking 1916 künstlerroman about the stories James Joyce told himself.

Ulysses, James Joyce.

The 1922 magnum opus about the stories that tell us.

Ficciones [Fictions], Jorge Luis Borjes.

The groundbreaking 1944 short-story collection about the stories we create that in turn create us.

Finnegans Wake, James Joyce.

The unclassifiable 1939 work that deconstructs the tyranny of stories once and for all.

Cien años de soledad [One Hundred Years of Solitude], Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Ground-zero of Magical Realism (a heavily disputed term); the novel is often treated as avant-garde, which is ironic, given how rooted in familial oral tradition Marquez insists it is (but then, according to Lloyd and Cleary, the Irish avant-garde was likewise firmly rooted in the oral and the traditional, and hence might serve as useful points of comparison).

El laberinto de la soledad [The Labyrinth of Solitude], Octavio Paz.

The famed 1950 essay collection by the Nobel-prize winning poet about how the Mexican, in his dual identity as both Spanish and Aztec, is representative of modern man altogether.

Song of the Simple Truth: The Complete Poems of Julia de Burgos.

Dual-language edition of the collected known works of Puerto Rico's national poet. Romantic. Liberatory. Free. In every sense of those words.

Complete Poems, William Butler Yeats.

Some days I seriously consider the possibility that I don't actually enjoy poetry, that I only muscle through it out of some misbegotten sense of English-major duty, that really I find it all forgettable at best, actively irritating at worst. Then I re-read Yeats, and I'm in love all over again.

Saturday, June 20, 2015

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment