L'Irlande et l'Amérique latine. This past week especially I've realized that the more I read of Irish and Latin-American literature, the more I have to account for France, of all countries. But first, let me get William Trevor out of the way:

Fools of Fortune, William Trevor.

Trevor's reputation is primarily that of a short-story writer and, well, it shows. This 1983 novel, as well-reviewed and critically revered as it may be, reads more like a collection of Trevor-esque short stories that happen to have recurring characters than a complete novel. (Between this and Kavanagh last week, I'm starting to wonder if maybe most writers should just stick to the one genre they're good at). The action bounces back and forth between England and County Cork (I'm noticing that a number of the texts I'm reading take place around Cork, making me all the more grateful that I visited there a couple weeks ago, and not Dublin). Three different characters provide the three separate, intertwining, first-person narratives; along with Beckett, Banville, Joyce, and others, I'm starting to see Lloyd and Clearys' thesis about the centrality of orality to Irish Modernism made manifest.

In a more continental theorist vein, Rene Girard seems to me to be the most relevant philosopher for interpreting this meandering text; a Big House of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy is burned to the ground by the loyalist Black and Tans, in revenge for a loyalist found killed on their property during the 1920 civil war--this novel begins, in other words, where Elizabeth Bowen's The Last September ends (another novel on my reading list that I already read for a class last Spring). This blaze kicks off an endless cycle of reciprocal violence between the English and Irish descendants of the mansion (Irish men take English wives throughout this text, consistently muddying up the ethnic strife, and rendering the two opposing sides the montrous double of the other, in Girardian terms). According to Girard, this cycle can only be short-circuited by a pharmakos, a scapegoat, which Girard sadly notes is difficult to find in our modern era.

Does it seem strange perhaps to bring in French theorist into an Irish text? I'm starting to think I don't acknowledge the French enough, as shown by the remaining texts I read this week:

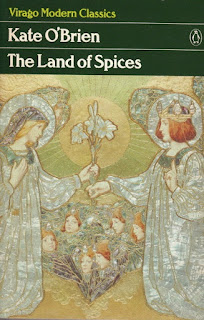

The Land of Spices, Kate O'Brien.

Kate O'Brien could be a pair with Edna O'Brien, whose Country Girls was likewise about young Irish girls and the vicissitudes of being schooled in a Catholic convent. Yet whereas the latter bitterly treated the nuns as primarily caricatures and obstacles, this excellent 1940 novel takes a far more nuanced, complex approach to nuns--Kate certainly does not romanticize convent life, nor sugar-coat the power-plays, petty rivalries, and power-dynamics that can dominate such a sphere. But she also presents the nuns as sympathetic human beings, doing, as all human beings do, the best they can given their circumstances.

The nunnery in question is specifically a French order, one headquartered in Belgium, and the text itself is littered with numerous French phrases, and at least 2 complete letters written in untranslated French whose content I had to guess at by context, as my very limited French comprehension was stretched to the max (goodness, I got back from Ireland wondering if I should maybe learn Irish Gaelic, do I need to get fluent in French, too?).

Though the novel takes place in Ireland at the turn of the 20th century, and often foregrounds the homerule movement gaining momentum at this time, the French connections never feel incidental; Ireland has long historical connections with France, seeing this nearby Catholic superpower as a potential ally against colonizing Protestant England. The Irish staged one of their many revolts during the French Revolution, erroneously hoping the new Republic would come to their aide while the English were distracted by the Napoleonic wars. There is a very complex relationship between the two countries, which the novel does an excellent job of matter-of-factly representing.

As for the actual plot? A surprisingly engaging one (for a novel about nuns); O'Brien got her career start as a playwright, and the way all the novel's action takes place in one self-contained, easily-staged location, as well as the excellent dialogue between characters and the Shakespeare plays staged throughout, shows her dramatic instincts. Though a very Irish text, the protagonist is actually an English-woman, the convent's Reverend Mother, who takes a young Irish girl with a troubled home life (a gambling gather, a drunken mother, a tyrannical grandma, a brother who dies in a swimming accident at one key part) named Anna under her wing.

The two forge a strong bond, and the Reverence Mother is who finally swoops to her rescue in the climax when her evil grandma tries to cancel out her recently-won University scholarship. Part of her leverage is her relationship with the local Bishop, who, though an ardent Irish homeruler who disagrees with her ethnically and politically, still share a mutual respect (something rare in Irish literature). Throughout the text, it is the nuns who must constantly negotiate between tradition and progress, the past and the future.

Aura, Carlos Fuentes.

And here the French appear again! France has very fraught historical connections with Mexico, too, particularly since Napoleon III tried to install Maximilian I as the puppet Emperor of Mexico during the 1860s (Cinco de Mayo, remember, specifically commemorates the Battle of Puebla, when the Mexican forces under Benito Juarez had their first major victory against France). Keeping with Fuentes' themes of the inescapable weight of history on modern Mexico, this 1962 novella likewise harkens back to the French invasion of Mexico. The rare book narrated in the second person, the text involves a young Mexican scholar (an aspiring historian) in Mexico City responding to a newspaper ad for someone fluent in French to come translate her husband's memoirs. There are numerous French phrases littered throughout (which likewise taxes my terminally limited French comprehension skills).

For 4,000 pesos a month, he will live with this old widow he realizes must be over 100 years old, as her decades-long dead husband is in fact a survivor from the failed French conquest of Mexico. Living with her is a young niece named Aura, who copies her Aunt's movements almost move for move. One intriguing scene involves him watching Aura skin a dead goat for dinner in one room, then run over to the other room to see the old widow following these same moves--a goat in Spanish is a Cabra, root of the premier Spanish insult Cabron, or "Big Goat," with heavy connotations of cuckoldry--and given how (SPOILER ALERT) Aura turns out to be the magical apparition of the old widow's younger self, and the scholar himself the unwitting re-apparition of the old French general (further demonstrating the long-lasting scars of history that persist a century after that traumatic event), the implied sex with younger versions of yourself is heavily foreshadowed in that skinned goat (which can also be a scapegoat, which brings us back to Girard) (given Vargas' Feast of the Goat and Healy's A Goat's Song, the recurring theme of the goat across Irish and Latino lit feels worth exploring).

Is it also worth noting that "Aura" in Spanish sounds very similar to "Ahora"--now--emphasizing the collapse of temporal disjunctions on parade in this text?

El reino de este mundo [The Kingdom of This World], Alejo Carpentier.

And the French yet again! And in another Dictator novel, no less! Last week I read Brian Moore's No Other Life, which featured a Haiti-stand-in called Ganae; but Alejo Carpentier's 1949 novel just features Haiti directly, focusing on a fictional slave named Ti Noël (somehow it seems referent that he's named after Christmas), who is present for both the slave era, the slave revolt, is sold to Cuba (Carpentier's home island), buys his freedom, then returns just in time to experience the brutal dictatorship (and eventual suicide) of Henri Christophe. This is intriguing, because it's not like Carpentier's native Cuba doesn't have its own fair-share of slavery and dictatorships to write about. Yet Carpentier, like Moore, finds himself fascinated by and inextricably drawn towards the Franco-Caribbean.

What is it that draws them? Is is Haiti's status as the only site of the only successful black slave revolt in European colonial history? Is it the Voodoo that permeates the legend of the country, which offers new possibilities for alternative religions, alternative epistemologies, even alternative ontologies? (The first part describes an escaped slave with a chopped-off arm who, legend has it, can metamorphose into any animal he wants to escape the whites who accuse him of poisoning the food; in the final part, where yet another Mulatto dictatorship replaces Christophe, Ti Noël actually does transform into different animals, interestingly). Perhaps the Franco-Caribbean intersects with the Hispano-Caribbean by means of their shared island of Hispañola--Haiti actually did conquer the Dominican Republic for a stretch and free its slaves; in slave times, each side of the island was called Sainte-Domingue and Santo Domingo respectively (man, what is it with St. Dominic anyways?).

In any case, Haiti's slave revolts and subsequent dictators clearly resonate with Latin-American experience, and has reverberation all the way in France and Ireland, too, where they all become enmeshed together (many Irish indentured servants escaped the Anglo-Caribbean to the Hispanic-islands, too, including in Cuba, further confusing and intertwining these three civilizations together).

Saturday, July 11, 2015

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment